My Burial beer name, not that you asked, is Precarious Bleakness on the Shoulders of the Orphan Clan.

You, too, have a Burial beer name. You can find it on the brewery’s website, via a handy name-generator chart. Then—who knows?—maybe yours can join the ranks among The Heavenly Atmosphere of Unrelenting Nothingness (an imperial dessert stout), The Lost Art of Anticipatory Infatuation (hazy double IPA), and The Endless Reception at the Table of Fellowship (pilsner).

That invitation to join the evolving creative experience that is Burial is as much a gag as the now-famous mural of Tom Selleck and Sloth on the exterior of their original taproom in Asheville, North Carolina. The fact that it’s a gag doesn’t make it any less welcoming. Yes, Burial is a business, working to attract customers and turn profits. It’s also one that’s honed a truly distinctive aesthetic over the years—the word “brand” feels crude, sometimes—meanwhile gathering one of the country’s most devoted followings.

Readers of Craft Beer & Brewing Magazine® have named Burial among their favorite small breweries in the country every year we’ve asked, ranking first in their size group in 2022. It doesn’t hurt that the beers tend to be great. Burial made our Best in Beer list two consecutive years, 2017 and 2018—an unprecedented feat. They’re still releasing fresh hits, such as the (more briefly named) Lightgrinder porter that scored 98/100 with our blind review panel earlier this year.

Implausibly, perhaps, the improvisational trio who founded the brewery in 2013 are still together, still running the business—though they’ve lately taken steps to empower more of their team, for their own health and that of the business. When small breweries last their first decade, as we know, the friends who start them don’t always stay friends; the couples who start them don’t always stay married.

That’s not to say that it’s always been easy.

“I’m happy to report that we’re all very human, and it’s been messy,” says Jess Reiser, Burial’s CEO. “And I even think that links back to Burial and who we are as a brand. … Nobody’s here pretending like we know what we’re doing all the time.”

“Nothing is as rosy as it seems,” says Doug Reiser, the COO. “Anything successful is challenging. … We do care about each other. And it’s really important to be open and transparent and fair with one another as much as you possibly can.”

They’ve succeeded in part because the three of them—the Reisers plus cofounder and head brewer Tim Gormley—encourage each other to pursue various projects about which they’re passionate, whether that’s wine, coffee, art, music, or supporting the local community.

Burial’s name comes from the New Orleans jazz funeral tradition—celebrating life while pleasing the spirits of the dead. “One of the beautiful things about starting a brand that’s about the human story—life and death and the pathway in between—is that you get to be as ubiquitous and distracted as you want to be,” Doug says.

The Residual Imprint of Nearly Illogical Beginnings

The New Orleans influence comes from the Reisers’ time there—Jess in graduate school, Doug in law school. After graduating in 2007, they moved to Seattle, where Jess worked for nonprofits and Doug practiced law.

Within a couple of years they’d befriended Gormley, who lured them down the craft-beer rabbit hole. He “already had a collection going at his house,” Jess says. “And he really turned Doug and me onto beer being something more than just facilitation of partying and socializing. It had history to it, it had obviously different flavors and styles. It had agriculture connections. It had branding and art and community to it, as well. So, the three of us just really started to bond over a common love of craft beer and Seattle.”

The trio turned their enthusiasm into a blog called the Beer Blotter, which increasingly plugged them into the brewing community. Gormley, meanwhile, left his job as a marketing analyst to work at Lazy Boy Brewing in nearby Everett. “Weekends,” he says, “doing whatever they needed me to do. Then I ended up being the first-ever full-time employee of that brewery and did a little bit of everything.”

Gormley hadn’t done much homebrewing, he says, so he thought, “I need to learn as fast as possible if I want to be doing this professionally.” The three of them pitched in on a 10-gallon system and started brewing weekly at Gormley’s place in the Ballard neighborhood. They were “just really loving the exploration that was offering us. Making some really terrible beer—but every once in a while, making a really good beer. And that just made us so excited.”

At the time, Jess was pregnant with the first of two boys, and she would show up “wondering where the hell we are and what we’re doing,” Doug says. “I would get distracted and go talk to her. I’m sitting on a stool in the driveway, not doing a damn thing, and clearly Tim is in the brewhouse doing all the work—which is pretty representative of our social structure. Tim was always the person who figured everything out, how to do it. And I was an idea person, constantly distracted with the social atmosphere of what we were involved in.”

A March 2010 trip to Belgium inspired them all. For Doug, another inflection point came a few months later, when a brewpub they loved in Port Townsend—Water Street Brewing & Ale House—shut down for good. Getting there via ferry was part of the fun, and the beer and food weren’t all that great. “But there was just something about the energy of the place that felt like [how] you would envision the Gates of Heaven. … It just felt like everybody was welcome.” When it closed, he thought: “‘Shit, places like this mean something to people.’ … As much as I loved the beer, I adored the taprooms more. For us, it was like, ‘We want to build a place where people can come and taste beers, and hang out, and have fun, and explore that element.’”

While Jess had earned valuable experience fundraising and marketing in Seattle’s nonprofit sector, Doug had gained confidence as an entrepreneur. “I don’t need an idea that I’m not interested in doing all the way,” he says. By then he had started two businesses in the legal and insurance fields, “so opening a third just felt easy. … In my head, I was like, ‘Okay, we’re doing this.’”

Gormley, meanwhile, had been learning the ropes at a modest commercial scale. “It just felt like we had this really nice collective knowledge that would lead us into figuring out how to start a brewery,” he says. It was Gormley who suggested Asheville. He had once visited a girlfriend there and liked it—it was outdoorsy, there was art, music, food. “It more or less ticked all the boxes of a place that I would want to settle in.”

“We made one visit,” Doug says. “We fell in love.” While Seattle’s scene felt fully developed, they saw opportunity in North Carolina. “Asheville was known as a brewery mecca,” he says, “and it had, like, six breweries.” Today, there are about 55.

In Asheville’s South Slope district, they bought the former transmission shop that would become their original taproom. One day in July 2012, their blog went silent … only to return in January 2013 with a post titled, “Why We Died: Burial Beer Co Comes to Life.”

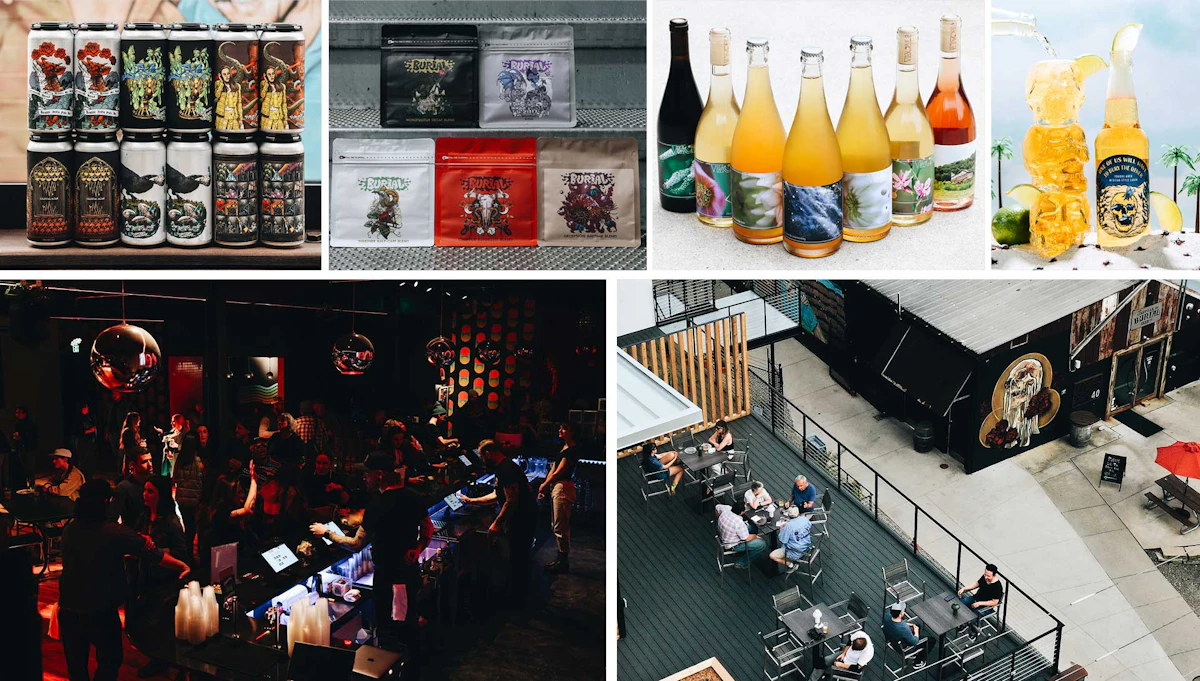

Top, left to right: Beer, coffee, and wine packaging; Bottom, left to right: The brooding energy of Eulogy; the rooftop Visuals wine bar overlooks the original brewery.

The Prolific Expanse of Descriptive Nomenclature

With Gormley working a one-barrel system, Burial sold somewhere between 100 and 150 barrels that first year. In 2024, the team is on track to brew about 16,500 barrels.

They began with no intention of brewing flagships, but today they have two core year-rounders: West Coast–ish Surf Wax IPA and Shadowclock Pilsner, German-inspired but with American corn. Those are the only beers available in sixers of 12-ounce cans. “They’re supposed to be gateway beers for people to first learn about our brand,” Doug says.

The others that go into distribution are mostly a changing selection of lagers and IPAs; the bigger IPAs, mixed-culture, and barrel-aged beers sell only at the taprooms. There’s no core hazy, Doug says. “In fact, until 2024, we never made back-to-back batches of a single beer, ever, at Burial. We decided to do that this year because distro pull had strengthened so much that we were just running out of beers immediately. So, we now rotate through some IPAs.”

For years, the wholesale-taproom split was close to 50-50 by volume. This year, they’re closer to 60-40 and getting more beer out to South Carolina and Tennessee. Besides direct-to-consumer sales and the occasional drop elsewhere, the Burial team is content to be in three states. “Where we wanted to be just so happened to line up with the exact territory of a distributor that we absolutely love and respect,” Doug says. “We’re in all their territories now, and that’s about all the beer we have.”

Those DTC sales are no afterthought—they view the online shop as their “seventh taproom,” Doug says. They dedicate staff to it and add personal touches to shipments, such as letters from the cofounders. “It actually does more business than one of our locations,” he says. “So, it’s absolutely necessary to our business model—not only financially, but connectivity-wise.”

Many of their online customers are people who previously visited or lived in Asheville. Burial ships to 15 states plus D.C., none farther west than Illinois— “staying in a place where we can get that box to you within a day or two,” Doug says, “so everything stays fresh, and you can have the beer experience you were hoping to have in Asheville.”

Since opening, they’ve brewed more than 1,600 different beers, including vintages and variations. I know what you’re thinking: That’s a lot of Burial beer names.

They started out by naming them after tools—think of a rusty old farmhouse implement that could be used for murder, and they likely ticked that box early on. “That was intended to make it simple and easy, and we thought we could go on forever,” Doug says. “I don’t even think we made it, like, nine months before we were like, ‘Oh my God. … Surf Wax? We’re onto board wax now?”

Soon they were using Bible stories depicted in Renaissance artworks, such as Massacre of the Innocents (famous Bruegel painting, also an IPA) or the Separation of Light from Darkness (Sistine Chapel panel, also a fruited farmhouse ale). “That was really where those names began,” Doug says. “And one day, Tim was like, ‘I think we could just make up our own names that sound like this.’ I think the first one we ever did was The Ocean Swallows the Sun, which was our first gose. From that point forward, it just became creative license.”

They soon found that these names resonated with customers. However, unlike the tongue-in-cheek name generator—which they insist they do not use to name new beers—Doug says the words need to come from “an organic feeling.”

“When I have handed people on our team the opportunity to come up with their own Burial product, and I can tell they’re thesaurus-ing words together, ‘I’m like, ‘Throw it away. Start over.’ I think the most impactful and powerful way that we’ve named beers is to just capture something said in the moment—write it down, and then come back to it later. And that is what I do. … But it’s got to be real. It’s got to be experienced. It’s got to be felt. And if you do that right, man, then the names hit, and they start to tell the story of a product that people get excited about. And that’s pretty much been the only rule behind how we do it.”

Left: The production brewdeck. Right: Burnpile music festival.

A Modern Ballad of Self-Discovery

While the cofounders remain passionate about beer, they’ve enabled each other to pursue interests that have broadened Burial’s reach as a business.

The embrace of farmhouse fermentations eventually led to natural wine—and their own wine label, Visuals, now with a rooftop wine bar. That bar sits atop their Eulogy music venue, next to the original taproom. Other musical entry points include collabs with local artists plus the annual Burnpile—part beer fest, part music fest. More recently, they’ve added a line of Burial-branded coffees.

Making wine from grapes followed logically from making it from apples. To make cider in North Carolina, they needed a winemaker’s license. “And that just opened the floodgates for us,” Doug says. But they knew they had a steep curve ahead of them.

“We went into wine knowing that we didn’t know much,” he says. They weren’t happy with what they fermented the first year. “We put it in a vermouth. I mean, the goal was to learn, right? And we always learn through connecting. We met an amazing winemaker who was willing to let us in, and that is always the best part.” (He says they aim to be equally open to others, as a brewery: “We don’t protect anything—strictly,” he says. “And all our staff know that.”)

By 2020, they’d decided that bringing grapes all the way from California didn’t make the most sense. “We were feeling like the quality was suffering a little bit through that process,” Gormley says, besides “losing the story that is so important—the terroir element. We were kind of muddying that up a little bit.”

So, they started partnering with the Ruth Lewandowski Wines in Sonoma County to have their Visuals wines made there. They’re currently selling about 1,500 cases of it per year. “Still pretty modest, but also not nothing,” Gormley says.

The Visuals wine bar opened in June 2024, atop the Eulogy Music Hall that opened seven months earlier. Jess describes Eulogy as a “music venue that is a Burial experience.” The cofounders view both as ways to welcome more people to Burial, “in the ways that make sense for them,” Doug says, “whether they’re into wine, or they’re into cocktails, or they don’t drink at all and they like music.”

The trio say they’ve greatly enjoyed the chance to work with some of their favorite musicians—including at the Burnpile Festival. The 12th edition was set for October 12 this year, featuring more than 60 guest breweries plus an indie-folk lineup led by John Moreland. (Due to the flooding after Hurricane Helene, the team moved this year’s festival to Charlotte.) Last year, they started leaning more into the Americana vibe with a lineup that included Deer Tick and MJ Lenderman. People responded. By sticking more or less to one genre, Doug says, they sold hundreds more concert tickets—and that was the goal. “We wanted to make the event approachable for the community here to say, ‘Hey, Burial can also help invest in bringing cool stuff to Asheville, beyond craft beer.’”

Their more recent foray into coffee began, as you might expect, with beer. One of Burial’s first hits in 2013 was Skillet, the “donut stout” with coffee. (Its popularity later spawned an annual spring event known as Skillet Six Ways, featuring a half-dozen flavored variations. “We never in a million years thought it would be what it [became] for our brand and our business,” Jess says. “Some of our most successful events and days throughout the years circle around the release of Skillet.”) Another early entry was Thresher, a coffee-infused saison introduced in 2014. The next year brought Griddle, an imperial coffee stout at 10 percent ABV.

Burial’s coffees, meanwhile, close the coffee-beer loop by assembling beans meant to be compatible with those beers—in their shop, you can buy bags of Skillet, Griddle, or Thresher coffee blends. “Beers are amalgamations of flavors,” Doug says. “They have a lot of different elements, so we kind of approach coffee the same way. How do we build a flavor profile from all these different beans, from different places, in different fermentations, different aging, and all those things?”

The brewery collaborates with Methodical, a roaster in Greenville, South Carolina, about 60 miles south of Asheville. That connection helped point the Reisers this past summer to Colombia, where they visited a favorite coffee farmer, to “work with him on some fermentation projects, some of which we’ve already tasted,” Doug says. “We were just back there for a cupping two weeks ago, so we could see the fruits of that project already. We’re buying those beans. That has been really fun.”

Now that they’ve established that “baseline” of blends, Doug says, they’re excited to be releasing some single-origin and single-lot coffees later this year. But here’s the kicker on the coffee adventure: It’s been more profitable than they expected.

“It was a fun idea, and it proved to be very intelligent, business-wise,” Doug says. “We sold a lot of coffee this winter. … It really helped make up for a lot of the downturn. We didn’t think about this as deeply as maybe we should have—it’s probably a bigger business investment, in a good way. It’s a potential revenue source, as opposed to it just being a cool merch item. So, we’re going to let it grow organically.”

As small breweries try to identify nonalcoholic offerings that make sense for them, Gormley says he’s surprised that more aren’t talking about coffee. The beer parallels are there: Besides the agricultural piece, it’s a sociable drink. “It’s experiential,” he says. “People going to a coffee shop—that’s an experience. … And it just feels like it fits our ethos in a lot of ways to lean into it.”

Left: Inside at Forestry Camp. Right: The Raleigh taproom.

An Offering to the Work of Righteousness

The Burial cofounders have established four core values: connectivity, courage, inclusivity, and integrity. Their charitable work arguably weaves through all four—though connectivity with the community is the most obvious thread.

“We started as a very small company,” Jess says, “and as we have grown, we’ve been very intentional about sharing those resources.” They call this work their Eternal Evolution Program, and it has four focus areas: the environment, food, housing, and mental health. “The idea is that those four pillars impact all of us as humans,” she says, as Burial works with “people and organizations to promote and support equitable access to resources.”

A recent and unexpected example came during the recent flooding after Hurricane Helene, when Burial—spared the damage that afflicted some other breweries—opened its doors to locals in need of food or electricity, while sending out recommendations on where to make donations.

For smaller businesses, it can be a challenge to figure out how to have the most impact. “We give 1 percent of our previous year’s revenue each year,” she says. “And what does that look like? … It’s not 1 percent of Amazon’s revenue, for example.”

What they’ve learned is that they can make a more palpable difference with smaller, grassroots organizations. Meanwhile, they have taproom space that can be used for fundraisers or other community events. Then they can lean into their relationships with those groups, Jess says, “to really get to know what they need and what would be most helpful.”

Those connections are the kind that strengthen a company, she says—whether it’s charitable groups or local artists, musicians, winemakers, coffee roasters, or fellow brewers. That connectivity piece is “woven so deeply throughout our company’s ethos, and something like that keeps the three of us—and, you know, most of our workforce—showing up every day.”

Note: All the subheads in this article are actual Burial beer names.