True to its name, Revision Brewing isn’t afraid to make hard decisions.

A clear-eyed approach has been part of the brewery’s DNA since year one, when the company scrapped its original plan to set up shop in West Sacramento, California, and instead went 140 miles northeast to open in Sparks, Nevada. Despite that significant initial speed bump, Revision was off to the races once it opened its doors in 2017.

Revision CEO and founding brewmaster Jeremy Warren learned much in the five years he spent opening and growing Knee Deep Brewing in Auburn, California, and he applied what he learned to his new venture. Accolades soon followed. Less than a year after its grand opening, Revision won gold and silver at the 2018 World Beer Cup in two of its most contested categories: American-Style India Pale Ale and Imperial India Pale Ale. With its reputation as a hop-centric powerhouse cemented, the brewery grew production volume by double and triple digits for its first three years, according to data reported to the Brewers Association, ending 2019 just shy of 20,000 barrels.

“They’ve really made a name for themselves with the liquid,” says Jon Thayer, sales and general manager of Mammoth Lakes, a distribution arm of Mammoth Brewing in Mammoth Lakes, California. (Mammoth distributes Revision’s beer in the area.) “They make some of the most award-winning and best IPAs in the world. We don’t have trouble getting them new shelf placements. People say, ‘Oh, it’s Revision. We’ll take it.’”

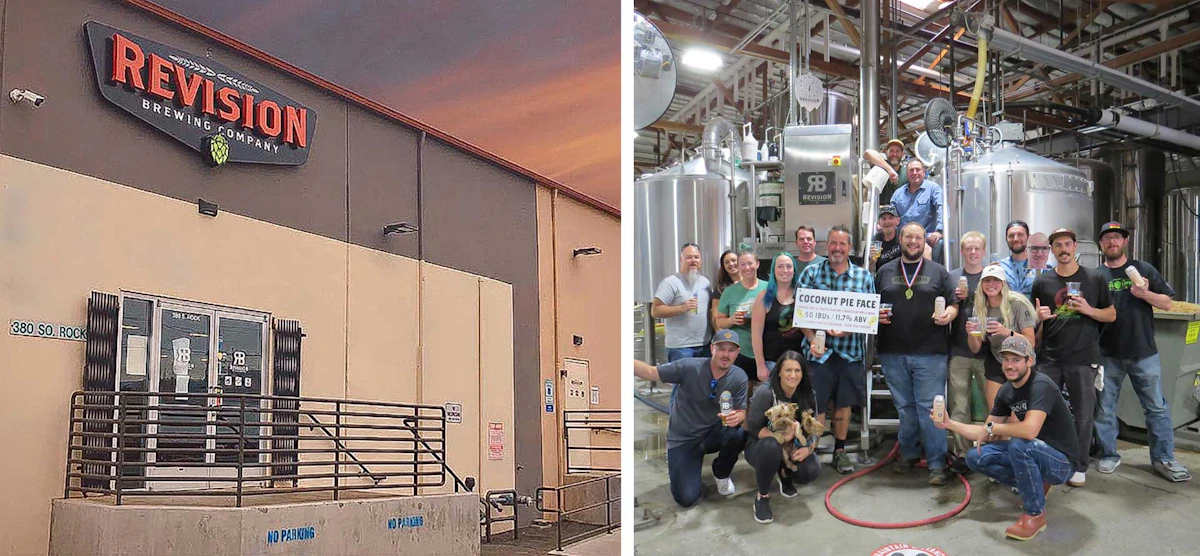

Revision’s current retail taproom.

Tough Adjustments

Those were the salad days for Revision: awards, sales growth, and distribution expansion to 16 states. Then came 2020. The pandemic’s closures of bars and restaurants dealt a lightning bolt’s shock to Revision, which in early 2020 was selling 55 percent of its beer to on-premise accounts. That year, annual production dipped for the first time in Revision’s brief history, to roughly 18,500 barrels. The company laid off staff while hiring for new sales roles—not a decision that any brewery wants to have to make.

With new and changing staff—now totaling 32 employees—the brewery also realized its human resources and company policies weren’t strong enough. In early 2022, the brewery instituted a multistate-compliant employee handbook, established clear policies about employee alcohol consumption, instituted new cross-department manager meetings, contracted a third-party human resources firm, and hired an outside agency to conduct point-of-view interviews with staff and management to identify areas of weakness or dissatisfaction.

Throughout this process, the brewery also underwent leadership changes and restructuring. It was painful at times, but Warren says that employee morale has since improved noticeably.

“You have to pull your team together and say, ‘We need to make some changes,’” Warren says. “Going through that, there is a lot of fear, but it turned out to be one of the greatest things that I feel happened to Revision.”

Warren regarded those HR stress points with the same tenacity he has applied to issues such as CO2 shortages and distributor consolidation. When discussing challenges for the business, he doesn’t shrink from admitting how difficult they’ve been—or from considering bold solutions. He says he often thinks about another brewery in the Reno area whose stylistic lineup never clicked with drinkers. Despite gentle criticism, that brewery’s leadership seemed to stick its head in the sand rather than face reality. The brewery closed, which Warren considers to be a cautionary tale.

“I’ve always had my ears open,” he says. “I’ve told any of my business partners, ‘I don’t care how much you love Revision IPA—if it doesn’t sell, we’re discontinuing it.’ We’re not going to be stuck on anything. You need to be willing to change.”

Turn and Face the Chains

The pandemic and its ripple effects set Revision on a new sales course, one that Warren says has made the company more sophisticated, cost-effective, and forward-looking.

Nor did that shift come without painful choices. When the pandemic damaged on-premise business and put greater importance on chain-retail sales, Revision laid off 11 employees. (The brewery offered to re-hire those former employees a year later, giving raises across the board.) Revision shifted roughly 95 percent of its sales to chain-retail stores at the height of the pandemic. That percentage has come down, as on-premise has normalized to a degree, but learning to play in larger retail accounts continues to benefit Revision. “It made us a healthier company,” Warren says. “We know how to operate [leaner and more efficiently], and we know how to handle change a lot easier.”

More recently, Revision invested in VIP sales-reporting technology and Nielsen data to inform its forecasts and planning. In October 2022 the brewery also hired a new director of sales Casey Brown, whose experience selling into chains comes from previous roles at Deschutes and FiftyFifty.

To Warren, it felt like scaling the brewery from a small craft mindset to a regional player overnight—with all the discomfort and investment that requires. Although Revision has sales in 16 states and four countries, northern Nevada and northern California account for 72.5 percent of the brewery’s overall sales. That’s by design because the farther a retailer is from the brewery, the harder Revision has to work to maintain its relevance with drinkers, and the more it struggles to compete with breweries in that area. Those local breweries—especially if they self-distribute—have more attractive prices for retailers. Revision then faces pressure to lower the prices for distributors.

“We have to analyze what the local breweries are doing, what margins our distributors work on, and try to bridge that gap as much as we can—but you really never can,” Warren says. “We’re not that large of a brewery, and we believe in quality versus quantity, so we’re not going to reduce our COGS [cost of goods sold] to compete.”

Instead, Revision has found success using blended margins: Revision IPA and Disco Ninja hazy IPA are the brewery’s volume movers, and it’s willing to take slightly lower margins on those. (Revision is comfortable having its core beers priced evenly with, or even a dollar above, its competitors’ standard four-pack price on the shelf.) Meanwhile, rotating brands have higher price points that balance margins out on those core beers.

“We don’t sell on price,” Warren says. “[But] we definitely use price as a model to get more beer sold.”

Revision’s distributors appear to agree with that strategy, and consumers don’t seem to mind the higher prices on some releases.

“They have a higher price point than a lot of other craft breweries in our area,” Thayer says. “At first it took a little time because that higher price point scared people away. Now, everyone associates the Revision name with a superior product.”

Maintenance Phase

When final tallies are in, Revision is likely to end 2022 having brewed roughly 23,000 barrels of beer. The brewery would max out its capacity around 26,000 to 27,000 barrels, but Warren says that would be “stressful,” and he’s not interested in pushing those limits.

Going forward, the brewery’s annual business plans estimate annual sales growth in the 8 to 10 percent range, which is more comfortable. The days of triple-digit growth seem to be in the rearview, and Revision’s leadership is more than fine with that, Warren says.

Not burdening the company with debt to finance growth was its saving grace, he says, allowing it to withstand COVID-era headwinds and sales fluctuations without being overleveraged. Retrospectively, though, Warren says the growth-obsessed mindset that sometimes pervaded the industry in years past came at a price: profitability.

“You’ll go in a negative [profit] direction the bigger you get sometimes,” Warren says. “If I was to go out to the production floor now and cut production by let’s say, 40, 50 percent, unfortunately we’d have to reduce some of our labor, but we’d still be profitable. If I cut production by 25 percent, I would actually be more profitable than where we’re at.”

That’s because a decline in production would increase demand for Revision’s beer, reducing the possibility that beer goes out of code and has to be destroyed. It would also allow the brewery to run a tighter ship by reducing the cost of goods and labor.

That’s not to say that Warren isn’t pleased to see that Revision has grown into a near-regional brewery with an international reputation for quality. He certainly is. However, he sees merit in stabilizing production levels, seeking out efficiencies, and focusing on profitability over eye-popping growth numbers.

It might even help him worry a bit less.

“If I ever did it again, definitely my business plan would be written differently now,” he says. “I would have realistic expectations of what the company will produce, and we wouldn’t exceed it. And hey, if we’re hitting that, let’s just have fun. I’d let go of all the stress of getting bigger and bigger and bigger.”